I don’t recall exactly when Bob Patterson entered my NC State life. Seems like he’s always been there. We have a lot in common. We’re both old, both got our doctorates from Cornell, both focused more on teaching than research and, most importantly, both care deeply about students and sustainability. He teaches his main class—STS 323, World Population and Food Prospects—in 2215 Williams, the auditorium across from his office, where I also taught conservation for several years. I’ve probably talked more with him over the years about important things than I have with all the faculty in my department combined.

But I’m not writing about Bob because he is like an older brother. I’m writing because I know what thousands of students also know—that Bob Patterson is an institution all his own, an institution as valuable as the corn and soybean crops he has nurtured. He’s been a faculty member here for half a century—literally, he became an assistant professor in 1968—teaching his heart out for longer than most faculty have been alive. A webssite about NC State without a chapter about Bob Patterson would be like Casablanca without Ilsa or Star Wars without Han Solo.

Bob is a professor in the Department of Crop and Soil Sciences. He’s worked on lots of crops all over the world. He is a true global thinker. At our recent lunch, I gave him a copy of my book, Nature’s Allies. It features a biography of Wangari Maathai, the Kenyan woman who won the Nobel Peace Prize for planting 50 million trees. He then told me about a time in the early 1980s when he was visiting Nairobi on a research project. He had learned about a Scottish agronomist who was doing work near there. Driven by his insatiable curiosity, he arranged to visit the scientist’s lab and field location to see his research. On the hour-long ride to the site, his taxi took him past groves of newly planted trees, with signs identifying them as Greenbelt Movement plantations. He asked his driver, who told him about Wangari Maathai. Since then, she has been one of his heroes. Mention anything, about anywhere, and Bob’s face will light up to either tell you about his related experience or ask you more, much more, about your own.

Our relationship began in earnest when we taught together at the Prague Institute—now newly re-christened as “NC State Gateway to Europe.” Bob was a regular there; I was a novice. In the summer of 2012, we stayed at the same hotel, so we generally started our days together over breakfast. He always—and I mean always—came into the breakfast room with something to share. He’d read an article about forestry and wanted to discuss it. He’d seen a strange fish at a market and wanted me to identify it. He was planning a field trip and wanted my advice on how to make it meaningful for the students (as if he needed my advice).

His field trips were famous, perhaps infamous. He and his students spent several days working at an organic farm out in the countryside. They slept in primitive cabins, got up early, ate down-home Czech food. They worked—planted, hoed, harvested—alongside the resident farmers, suffering the heat, rain and bugs just as the farmers did. “Think and Do the Extraordinary” is our current campus slogan, something Bob and his students lived for years. They came back caked in mud, exhausted—and radiant. Study abroad is transformative, we know; study abroad with Bob Patterson is extraordinarily transformative.

Bob told me about the origin of his principal course, World Population and Food Prospects. Just after he joined the NC State faculty, legendary Chancellor John Caldwell got together a group to discuss adding cross-disciplinary courses that both students and faculty members had been demanding. It was the late 1960s, and students were demanding all sorts of things, including interesting courses. But the time was also the height of the Cold War and the emergence of the environmental movement. The committee agreed on three courses as priorities—Nuclear Proliferation, Humans and the Environment, and World Population and Food Prospects. Bob, his colleagues said, you’re the agronomist, so you teach about food. He first taught the course in 1970, with three other faculty. Soon, however, the other teachers’ department heads made waves about them teaching a non-major course, and they all backed out. Bob took it over himself in 1974 and has taught it ever since, every semester, first to about 60 students per year, now to about 200 students per semester.

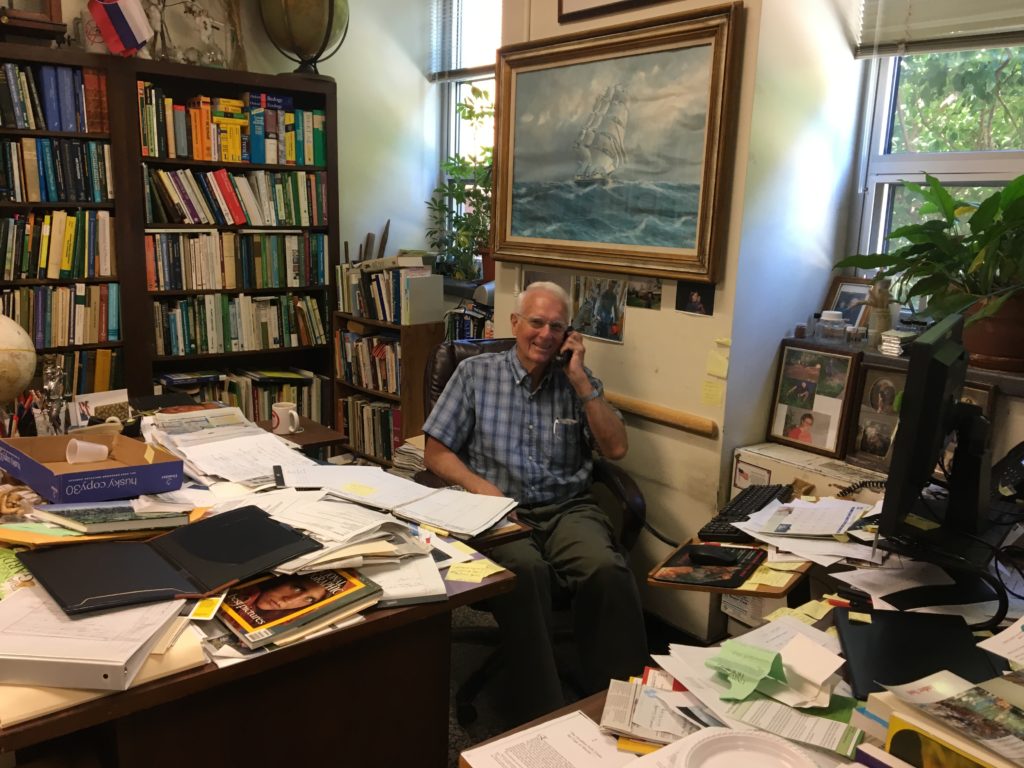

Bob is not a modern faculty member. New faculty members tend to have sleek, modern offices with minimalist furnishings that look like interior-decorating photo shoots. Not Bob. His office is packed—lined floor to ceiling with shelves bulging with real books; the desk and work table covered in stacks of journals and newspaper articles; the walls plastered with overlapping layers of photos, sayings and hand-drawn pictures; the door covered in notices of upcoming (and often long past) events. Seed pods, stalks of leaves and soil samples mix with souvenirs of international travel on random surfaces. Plants grow in front of the windows. Drop in and he’ll say, “Ah, I’ve got something here I was wanting to ask you about…” and pull an article off one of the stacks to share. “If you have time, please read this and tell me what you think.” Most of us these days regard paper as our enemy, but to Bob it is an old friend. Walk into 2212 Williams Hall and you know you’re in a faculty office, not in some corporate think-tank.

His office is like Grand Central Station. A student worker is usually posted in the outer room, prepping his handouts for class and fending off random visitors (like me). It doesn’t help. Everyone has business with Bob. Advisees need advice, Park Scholars need mentoring, club leaders need the upcoming program confirmed, staff and junior faculty need signatures and some wisdom, former students need hugs.

To Bob Patterson, “professor” isn’t a job, it’s a mission. “My parents wanted me to do something no one in the family had done—get a college education,” he told me. “I came down to State as a student, scared to death.” But he got over the fear and kept at it, and he hurried right back here after completing his doctorate at Cornell. Since then, he’s won about every teaching award the university, the UNC system and the agriculture profession have to offer. He was designated an Alumni Distinguished Undergraduate Professor in 1981; although no good records exist, the Provost’s Office assured me that he is probably the oldest ADUP still working—and still eager to inspire the next class of students.

Inspiring is not a compliment I use lightly or often, but Bob earns it. Once I asked him to speak to a group of doctoral students from Brazil, England and NC State whom I was hosting for a nine-day seminar on climate change. Of course he said yes. He talked about the need to preserve the biodiversity of old cultivars of plants—heritage crops, they are called—that might be more adaptable to the hotter, drier climate that is coming. He described the international seed bank that the United Nations had established in Aleppo, Syria. Then he talked about how wars and unrest in the Middle East had destroyed that city—and the seed bank. Most of us were crying, including Bob, for the damaged lives of those people and the damaged sustainability of our earth.

No, Bob Patterson is not a modern faculty member. He doesn’t flip the classroom, avoids powerpoints with background music and embedded video and has trouble sticking to the syllabus. What he has is fifty years of deep and broad knowledge about people and the world. What he has is sincerity and caring that transcends all the new-fangled ideas of pedagogy.

Many times, I talked with students who were taking both his course and mine. Invariably they would explain, without knowing it, what separates Bob Patterson from the rest of us: “I really like your course, but I Love Dr. Patterson.”